Half an hour away, in the mostly Druze town of Hasbaya, 85-year-old Abu Nabil sweeps the street outside his shop.

The Druze faith is an offshoot of Islam, with adherents found in Lebanon, Syria, Israel and Jordan.

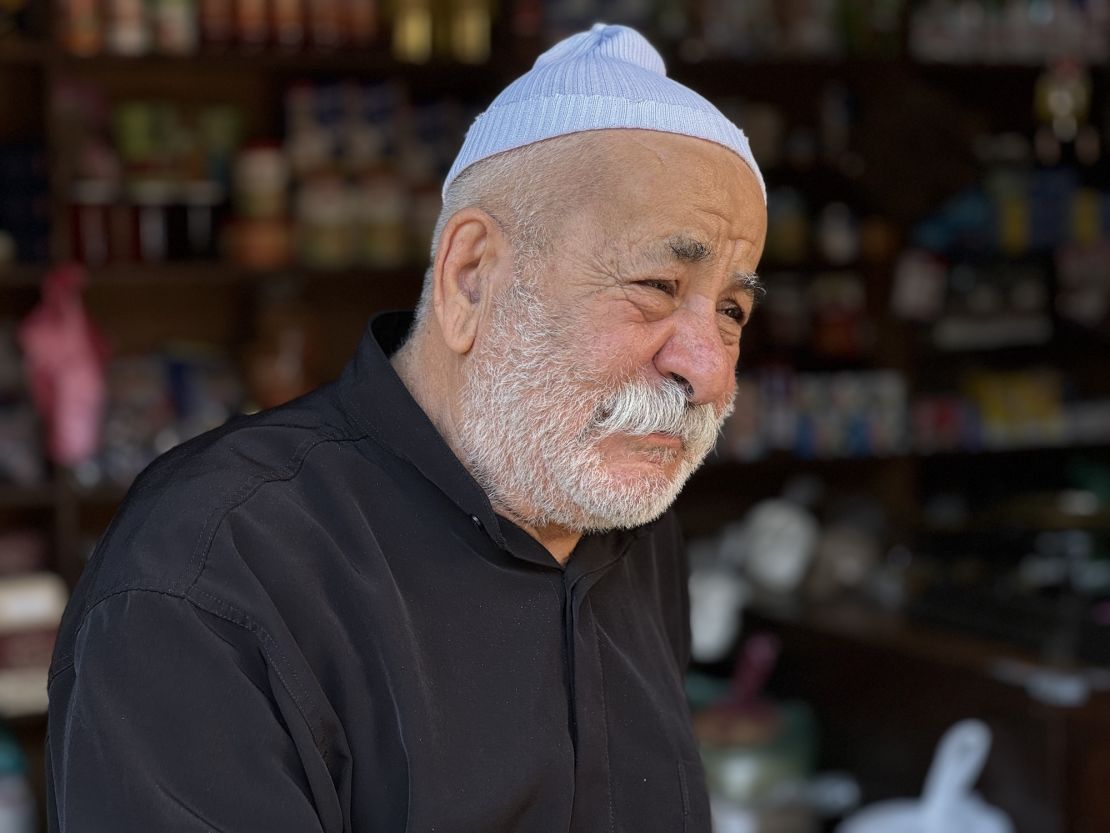

A pious man with a gentle smile and a bushy white moustache, he looks on the bright side of life. “The Lord is merciful to us,” he says. “We can sleep in our homes. We eat. We drink. No one goes hungry.”

85-year-old Abu Nabil, a resident of the town Hasbaya

Since his birth, Abu Nabil saw Lebanon gain its independence from France in 1943, prosper during the 1960s, become engulfed by civil war, invaded and partially occupied by Israel for decades, and partially occupied by Syria, also for decades.

He has seen the country emerge from civil war, embroiled in war again with Israel in 2006, wracked by a string of high-profile assassinations, convulsed by a short-lived revolution in 2019, followed by economic collapse, and now once again, on the brink of full-scale war with Israel.

“War is ruinous,” he says, grasping my hand. “In war, everyone loses, even the winner.”

Across the street, young men drink coffee from small paper cups while smoking cigarettes. They don’t want trouble, they say, declining to be interviewed.

The worry here, and in many parts of Lebanon, is that if you speak out against Hezbollah, there could be a price to pay. Some people do, some politicians do, but when Hezbollah lives nearby, it’s best not to take the risk.

“Gaza is not my war, and I don’t want to pray in Jerusalem,” one of the men insisted.

Another said one of reasons not one Israeli missile, bomb or artillery round has landed in Hasbaya is because young men act as a sort of armed community watch, making sure no one, neither Hezbollah nor Hamas, fires anything at Israel. It’s not their turf and they’re not welcome here, they say.

Down the hill, there’s a traffic jam on the road leading out of Hasbaya west towards Marjayoun. Cars crawl at a snail’s pace, drivers sticking their heads out to see what it’s all about.

A large group of men, women and children stand around a new white stone building, all dressed in their best. Parked in front is a shining white convertible, the bonnet covered with bouquets of flowers and a license plate reads, in English, “Newly Married.”

A group of men arrives in traditional Druze clothing—with small turbans, vests and low-crotched trousers—carrying drums and horns.

As people leave the building, musicians strike up a raucous tune with a heavy beat and high notes, while others twirl prayer beads over their heads.

The bride, Fatin, in a long lacy dress, and the groom, Taymour, emerge into the sunlight, and everyone cheers.

I decide not to interfere with annoying questions about Israel, Hezbollah, impending war, death, destruction and displacement. Everyone is happy, enjoying the bright June afternoon, the noise, the presence of friends and relatives. “Why spoil such a beautiful day?” I think.

Looking at the festivities, you’d never guess that Israeli forces are only about five miles away and that, not far from here, deadly projectiles are being hurtled back and forth across the border.

The irony, however, was not lost on one man, who leaned over with a chuckle, “We’re celebrating here while war is around the corner.”